In South Korea, as well, historians say that Carter adopted the messaging of a military government facing human rights criticism.

In May 1980, a student-led pro-democracy uprising in the South Korean city of Gwangju was met with a brutal crackdown. In a single day, 60 people were killed and hundreds injured.

Journalist Timothy Shorrock, who has been reporting on US-South Korea relations for decades, said that the Carter administration was wary of losing a useful Cold War ally and, therefore, threw its weight behind the military government.

He explained the US supported the South Korean leadership by freeing up military resources that allowed troops to put down the uprising.

“Knowing that [military leader General Chun Doo-hwan’s] forces had murdered 60 people the day before, they still believed this uprising was a national security threat to the United States,” Shorrock said of the Carter officials.

He added that when a US aircraft carrier was sent to the region, some protesters convinced of US rhetoric on democracy and human rights believed that the US was coming to intervene on their behalf.

Instead, the carrier had been deployed to bolster the US military presence so that South Korean troops at the demilitarised zone with North Korea could be reassigned to put down the uprising.

Shorrock says that contingency plans even included the possible use of US forces if the unrest in Gwangju spread further.

While there is no universally accepted death toll for the uprising, the official government figure is that more than 160 people perished. Some academic sources put the death toll at more than 1,000.

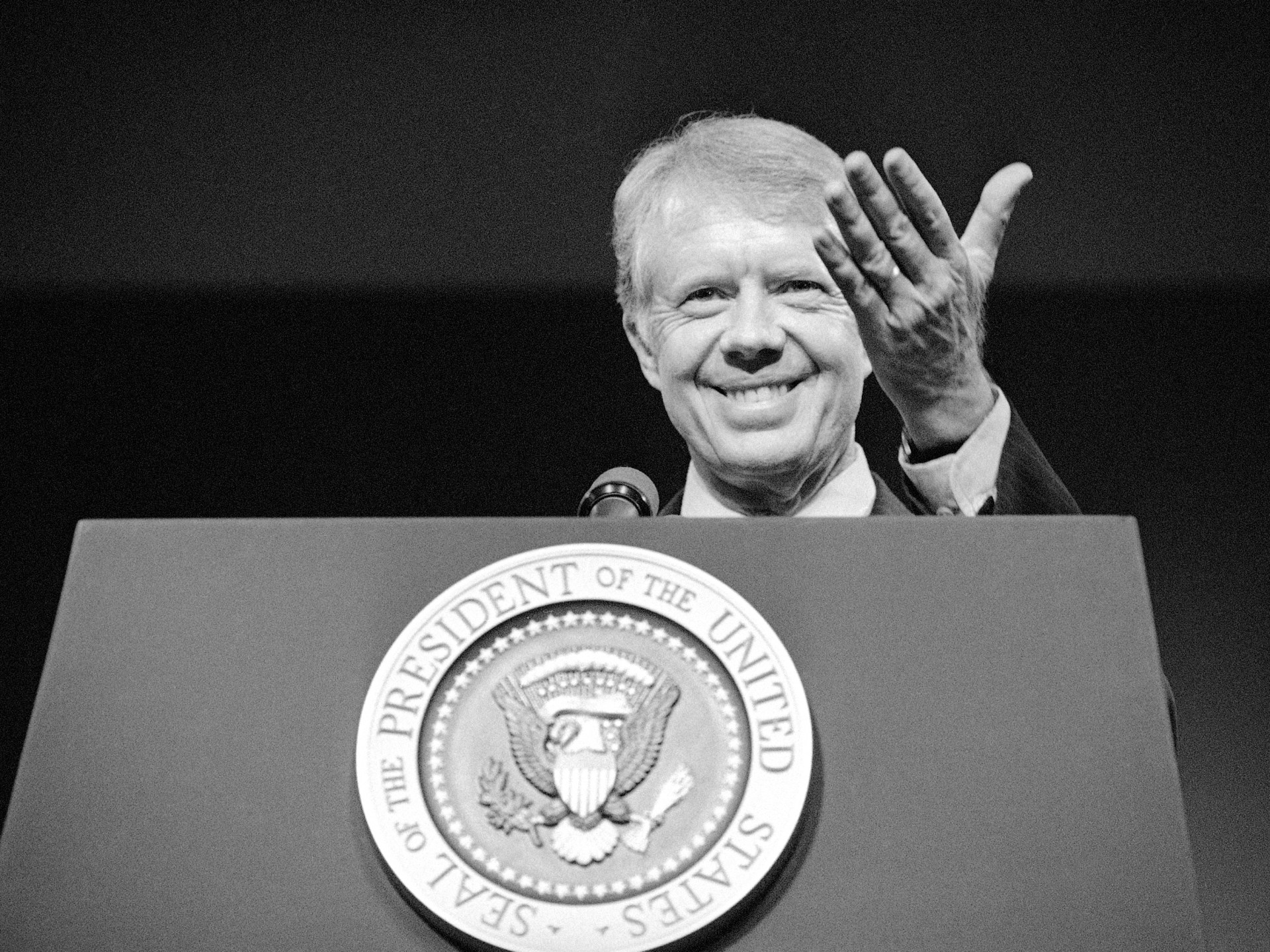

Asked by a reporter if his actions had been at odds with his professed commitment to human rights, Carter said that there was “no incompatibility”.

He asserted that the US was helping South Korea maintain its national security against a threat of “communist subversion”, mirroring the rhetoric of the country’s military leadership.

It was the kind of rhetoric that South Korean leaders had long used to justify repressive and antidemocratic measures.

When South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol declared martial law in December 2024 in the name of combating “antistate forces”, many drew parallels to the traumatic events of Gwangju.

“What he was saying at the time was what General Chun Doo-hwan was saying, characterising this as a communist uprising, which it was not,” said Shorrock. “He never apologised for that.”

Related News

Iran to hold nuclear talks with France, UK, Germany on January 13: Report

Yemen’s Houthis hit Tel Aviv, Israel, with missile

Luigi Mangione pleads not guilty to ‘terrorism’ in US healthcare CEO murder